di Ivan Quaroni

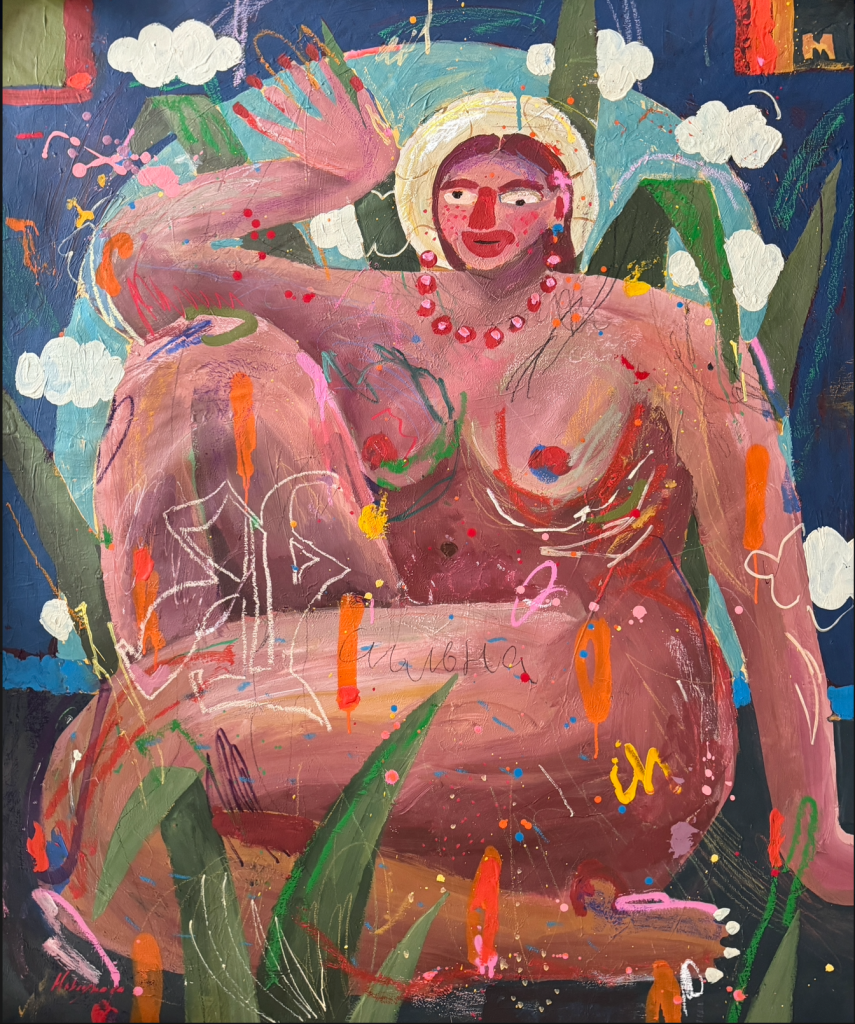

My native land, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 235×95 cm

Tra paesaggio e identità nazionale esiste una relazione che spesso sfugge a chi è abituato a considerare il primo semplicemente come una estensione dell’ambiente naturale. Secondo la Convenzione europea del paesaggio, un documento promosso dal Consiglio d’Europa a Firenze nel 2000, a cui hanno aderito 40 paesi, tra cui l’Ucraina, “esso designa una determinata parte del territorio, così come è percepita dalle popolazioni, il cui carattere deriva dall’azione di fattori naturali e/o umani e dalle loro interrelazioni”. Ciò significa che, come tutte le cose plasmate dall’uomo, il paesaggio è un luogo carico di memorie, proiezioni, aspettative e significati che possono tradursi in valori identitari o nazionali.

La pittrice ucraina Iryna Maksymova interpreta emblematicamente questo aspetto del paesaggio, trasfigurandolo in un immaginario visivo che attribuisce al corpo umano (soprattutto femminile) un ruolo centrale nella programmatica rappresentazione della forza e vitalità di una nazione assediata. Sul corpo, e dunque sull’esperienza concreta e sensibile della realtà, si fonda, infatti, il concetto di appartenenza al paesaggio e, per estensione, all’identità culturale e nazionale.

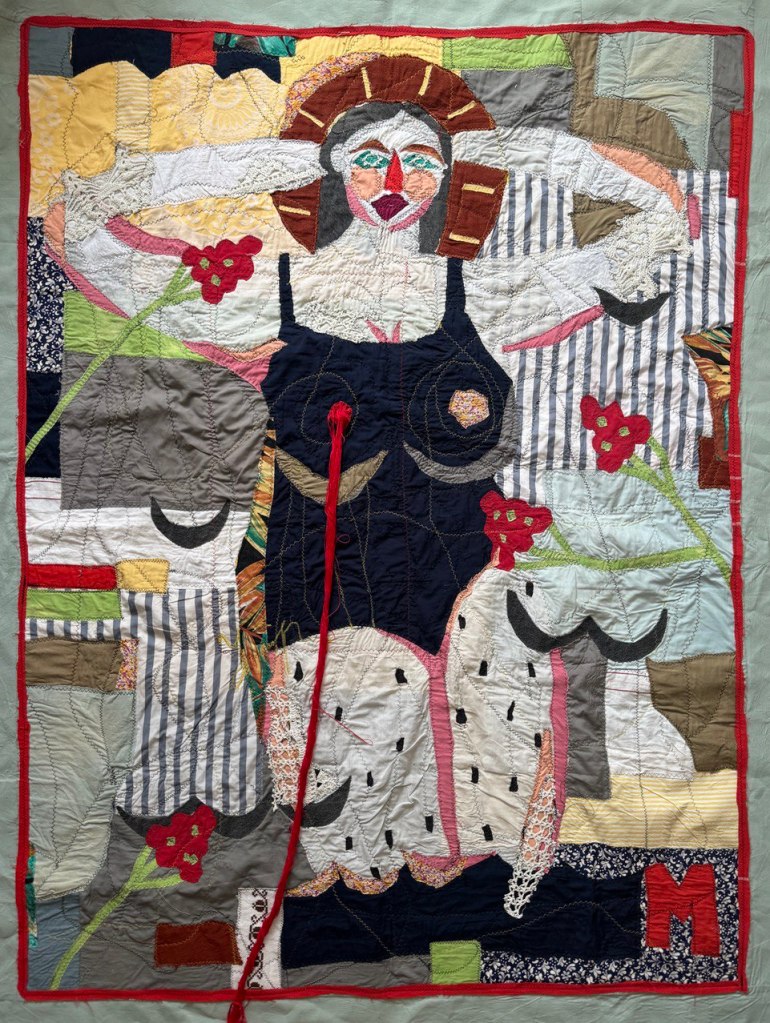

Divka, 2024, textile, 155×130 cm

Nativa di Kolomyia, una cittadina nella provincia di Prykarpattia caratterizzata dalla presenza di una forte tradizione legata alla pittura popolare e alle produzioni delle arti applicate, Iryna Maksymova traduce il proprio interesse per il folclore ucraino e per l’arte ingenua in un lessico figurativo capace di combinare le suggestioni del passato con le urgenze del presente. Nei suoi dipinti e nei suoi arazzi tessuti a mano il tema dell’identità nazionale si sovrappone a motivi legati all’emancipazione femminile e alla sensibilità ecologica, sfociando in una dimensione estetica che attinge tanto all’arte degli outsider quanto alla cultura visiva del graffitismo esteuropeo (di cui fanno parte anche i connazionali Aec e Waone, del duo Interesni Kazki).

Don’t bother, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 120×95 cm

Il titolo di questa mostra, Landscape’s Body, si riferisce in particolare alla riflessione sulle ferite e le modificazioni subite dal territorio ucraino a causa della guerra con la Russia. La recente produzione di Iryna Maksymova ruota attorno alla rappresentazione simbolica del proprio paese. L’artista prende spunto sia dalla fonetica femminile di parole come “Paese” (країна) e “Ucraina” (Україна), sia dalla personificazione, anch’essa femminile, della “Madre Patria”, così come è rappresentata nel gigantesco monumento de-sovietizzato che guarda verso est, dalle colline che sovrastano la sponda destra del fiume Dnepr, dove sorge la Kiev storica. Da qui deriva la rappresentazione di figure femminili che incarnano il vigore e la vivacità di una nazione resistente, che non si lascia abbattere dalle drammatiche vicende belliche.

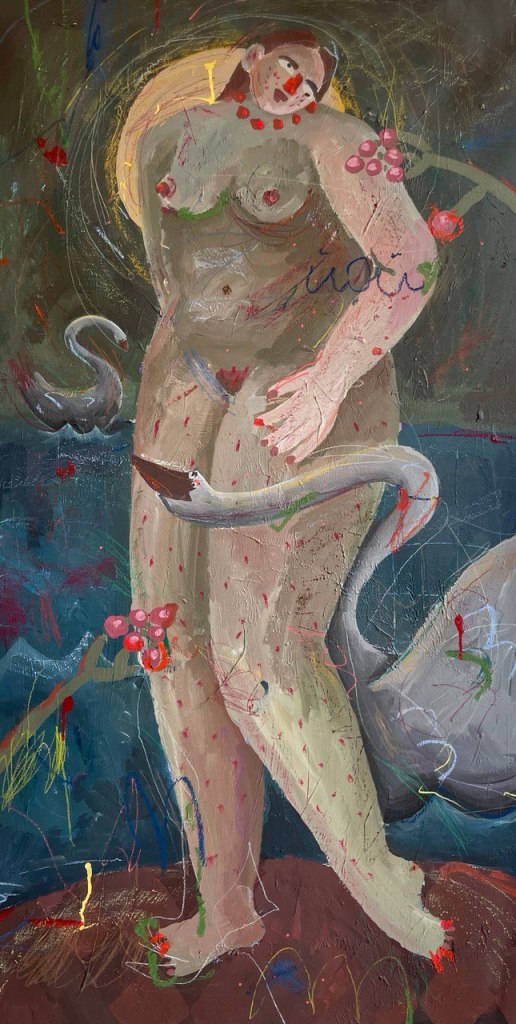

Quelli dipinti da Maksymova sono nudi di ragazze e donne dalla fisicità prorompente, dee di un Olimpo rivisitato, come la Leda di Becoming a Swan o le orgiastiche Muses, che celebrano il lato panico ed erotico dell’esistenza, abbattendo pregiudizi e tabu che da secoli stigmatizzano la fisicità femminile. Ma sono anche fanciulle innocenti, giovani indifese protette da temibili guardiani, come gli animali custodi del dipinto Safekeeper e dell’arazzo Little Princess.

Safekeeper, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 95×95 cm

L’artista usa un linguaggio pittorico semplice e immediato di matrice neoprimitivista, dove il segno espressionista e gestuale si fonde con la naïveté di pittori autodidatti come Mariya Pryimachenko, la cui arte è intimamente legata al folclore e alla cultura rurale dell’Ucraina. Come la Prymachenko, infatti, anche Iryna Maksymova rappresenta spesso animali reali o fantastici (come, ad esempio, il mitico Pegasus dell’arazzo omonimo), caricandoli però di significati simbolici e talvolta politici.

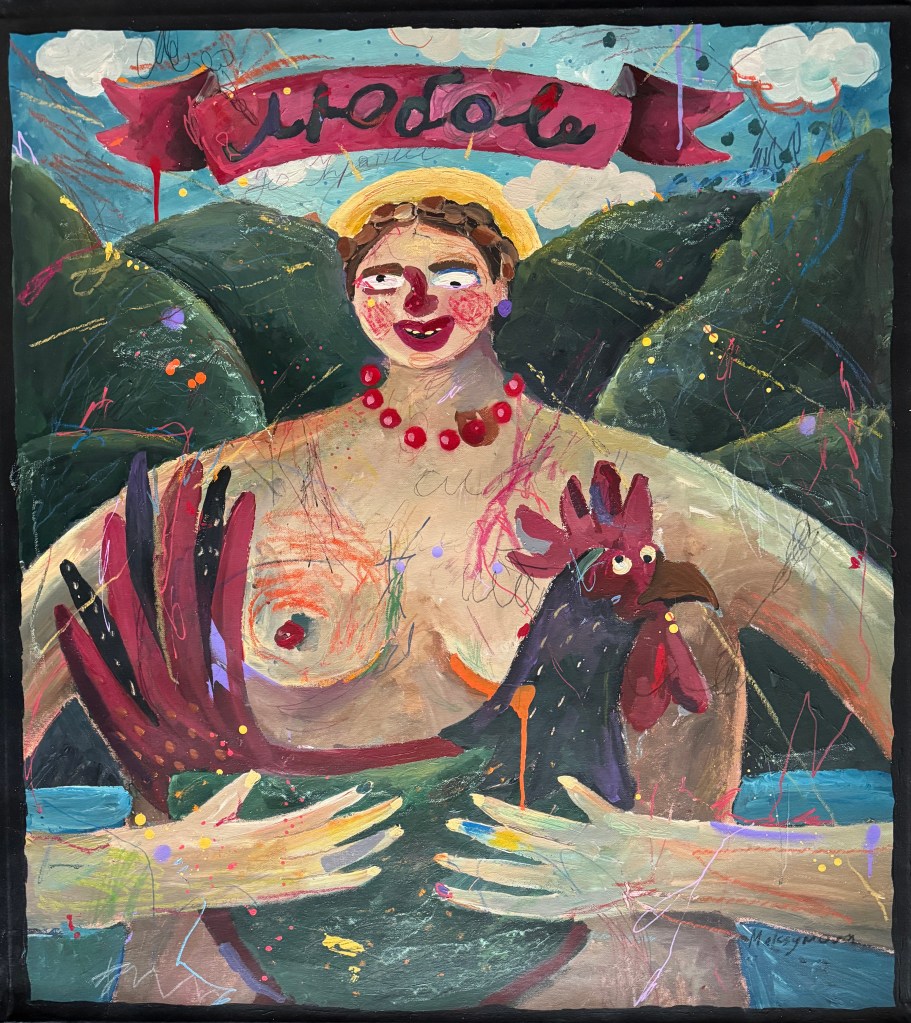

Il suo bestiario, composto da creature senzienti, in un certo senso equiparabili all’uomo, rappresenta, in realtà, una radicale critica alla cultura antropocentrica, principale responsabile delle violenze perpetrate sugli animali. Nell’opera di Maksymova, in certi casi la rappresentazione zoomorfa si inserisce nel quadro di precisi temi iconografici – come, ad esempio, il cigno del mito di Leda (Becoming a Swan) o il biblico serpente tentatore in Conscience -, in altri, invece, trae spunto dalla cronaca, come nel caso del gallo raffigurato nell’acrilico su tela intitolato Symbol, che ricorda quello in ceramica, diventato uno dei simboli della resistenza ucraina dopo la pubblicazione di una foto dei bombardamenti di Borodianka, divenuta virale nel web. Nell’immagine si vede una caraffa a forma di gallo rimasta intatta sulla mensola di una cucina di un appartamento divelto dalle bombe. Curiosamente, quel vaso a forma di gallo è opera dello scultore ucraino Prokop Bidasiuk (1895), le cui opere sono state esposte al National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Arts di Kiev.

Symbol, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 105×95 cm

D’altra parte, come dice l’artista, “Con le mie opere figurative e naïf, io do voce ai problemi del mondo che mi toccano personalmente e cerco di promuovere l’uguaglianza e l’interconnessione, sviluppando, allo stesso tempo, i motivi tradizionali del folclore ucraino in nuove forme visive”. Come nel dipinto Holubka Dance, dove il motivo della popolare danza nuziale “Holubka” (che in italiano significa “colomba”) si trasforma in un’occasione per sostituire il paradigma classico della coppia in una più avventurosa esperienza orgiastica. Altro tema iconografico legato al folclore ucraino è quello delle bacche di Kalyna, disseminato in molte opere dell’artista, sia nella naturale forma vegetale in Mother, Becoming a Swan, Cat e Conscience, e sia in foggia di perle nelle collane che cingono i colli delle sue eroine in Don’t Bother, In the Wild Woods e Muses.

La Kalyna (o Viburnum Opulus) è un albero da fiore che cresce in Ucraina ed è conosciuto fin dai tempi antichi, quando si credeva che avesse il potere di donare l’immortalità e di unire le generazioni nella lotta contro il male. Le sue bacche di colore rosso ornano i ricami, i gioielli e perfino il costume nazionale delle donne ucraine ma, soprattutto, sono celebrate nella canzone Ой у лузі червона калина (“Oh, viburno rosso nel prato”), un brano patriottico scritto dal compositore Stepan Čarnec’kyj nel 1914, divenuto poi l’inno dell’Esercito Insurrezionale Rivoluzionario Ucraino tra il 1918 e il 1921, e, in seguito, ripreso da David Gilmour dei Pink Floyd nella cover intitolata Hey, Hey, Rise Up!, a sua volta ispirata alla versione a cappella della band ucraina BoomBox, che l’ha cantata in tournée negli Stati Uniti proprio il 24 febbraio 2022, giorno in cui è iniziata quella che Putin ha definito eufemisticamente una “operazione militare speciale”.

Holubka Dance, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 140×120 cm

Nelle opere di Iryna Maksymova, la simbologia delle bacche di Kalyna, simbolo della passione e vitalità del popolo ucraino, è anche un’allusione allo spargimento di sangue provocato dalla guerra in corso. In generale, le simbologie usate dall’artista sono sempre duplici, interpretabili sia in senso tradizionale, che in riferimento ai fatti dell’attualità e della cultura contemporanea. Ad esempio, la creazione di arazzi cuciti a mano recuperando scampoli di tessuti è un chiaro riferimento alla produzione tessile del folclore ucraino, ma è, allo stesso tempo, il segno della sensibilità ecologica dell’artista e della sua volontà di evitare ogni spreco attraverso l’upcycling, una pratica creativa che, a differenza del comune riciclo, basato sulla trasformazione dei materiali in nuovi prodotti, conserva le proprietà degli oggetti, reimpiegandoli in modo da essere chiaramente riconoscibili.

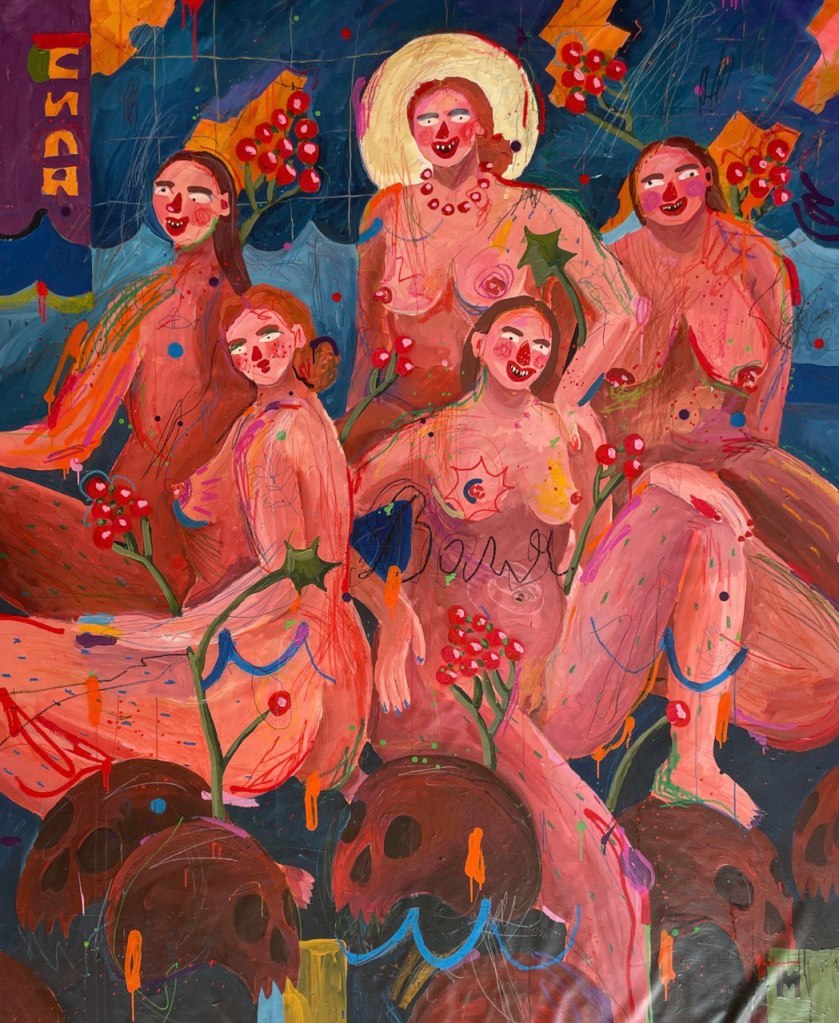

Questo è anche il motivo per cui, dovendo sfruttare pattern e texture dei tessuti, negli arazzi, l’impronta gestuale della pittura di Iryna Maksymova sembra lasciare il campo al carattere ornamentale tipico delle produzioni tessili tradizionali. Anche il dipinto intitolato Odesia, raffigurante un gruppo di donne discinte posate su un cumulo di teschi e incorniciate da grappoli di bacche di Kalyna, può essere variamente interpretato. Da una parte, infatti, il quadro richiama l’immaginario tipico dell’artista, con le sue prorompenti figure femminili che esibiscono fieramente la propria fisicità, dall’altra fa esplicito riferimento, fin dal titolo, alla città portuale considerata la perla del Mar Nero. Odessa, antico crocevia tra Oriente e Occidente, fondata nel XVIII secolo da un napoletano di origini spagnole dove un tempo sorgeva l’insediamento dell’antica colonia greca di Odesso, negli ultimi due anni è stata oggetto di ripetuti attacchi aerei e missilistici russi. Certo, nel dipinto non c’è alcun riferimento diretto a questi fatti, ma allora, come interpretare la presenza di quei teschi?

Mother, 2023, textile, 175×130 cm

Iryna Maksymova è evidentemente una pittrice che si avvale di simboli e metafore per raccontare una realtà, quella dell’odierna Ucraina, sospesa tra i fantasmi del passato, gli orrori del presente e le speranze di un futuro migliore. La sua opera riesce ad essere politica pur senza scadere mai nel didascalico. A differenza dell’arte prodotta da tanti “Artivisti” contemporanei, spesso esteticamente brutta o insignificante, la sua arte non rinuncia alla bellezza. Il segno pittorico selvaggio e gioioso dei suoi dipinti e le raffinate trame tessili dei suoi arazzi sono le armi con cui Iryna Maksymova incanta lo sguardo dell’osservatore rendendolo, simultaneamente consapevole del dramma che affligge il suo paese. La dimostrazione che la seduzione è, quasi sempre, il miglior modo per trasmettere un messaggio.

Iryna Maksymova. Landscape’s Body

by Ivan Quaroni

A relationship exists between landscape and national identity that often escapes people who are accustomed to thinking of the former as merely an extension of the natural environment. According to the European Landscape Convention, a document issued by the Council of Europe in Florence in 2000, undersigned by 40 countries including Ukraine, “the landscape is part of the land, as perceived by local people or visitors, which evolves through time as a result of being acted upon by natural forces and human beings.” This means that like all things shaped by man, the landscape is a place charged with memories, prospects, expectations and meanings, which can translate into identifying or national values.

The Ukrainian painter Iryna Maksymova emblematically interprets this aspect of landscape, transfiguring it in a visual imaginary that assigns a central role to the human body (above all female) in the programmatic representation of the force and vitality of a besieged nation. The concept of belonging to the landscape and, by extension, of cultural and national identity is therefore based on the concrete, perceptible experience of reality.

In the wild woods, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 145×95 cm

Born in Kolomyia, a city in the province of Prykarpattia known for its strong tradition of folk painting and the production of arts and crafts, Iryna Maksymova translates her interest in Ukrainian folklore and naïve art into a figurative lexicon capable of combining impressions of the past with the urgent issues of the present. In her paintings and hand-woven tapestries the theme of national identity overlaps with motifs connected with women’s liberation and ecology, enabling an aesthetic dimension that draws on outsider art as well as the visual culture of Eastern European graffiti and street art (also in the work of fellow countrymen AEC and Waone, of the duo Interesni Kazki).

The title of this exhibition, Landscape’s Body, refers in particular to reflections on the wounds and changes inflicted on the Ukrainian territory by the war with Russia. Iryna Maksymova’s recent production focuses on the symbolic representation of her country. The artist takes her cue from the feminine phonetics of words like “country” (країна) and “Ukraine” (Україна), as well as the personification, again in feminine terms, of the “Mother Country,” as represented in the gigantic de-Sovietized monument that looks eastward from the hills above the right bank of the Dnepr River, the location of historic Kyiv. The result is the depiction of female figures that embody the vigor and vivacity of a resistant country, that does not let itself be overwhelmed by the dramatic developments of the war.

Little Princess, 2022, textile, 170×140 cm

Maksymova’s works are nudes of girls and women with abundant physiques, deities of a revisited Olympus, like the Leda of Becoming a Swan or the orgiastic Muses, which celebrate the Panic and erotic side of existence, destroying the prejudices and taboos that have stigmatized female physicality for centuries. But there are also innocent maidens, protected by fearsome guardians, like the tutelary animals of Safekeeper and the tapestry Little Princess.

The artist utilizes a simple, immediate pictorial language based on a Neo-Primitivist matrix, where the expressive and gestural approach blends with the naïveté of self-taught painters like Mariya Prymachenko, whose art is closely tied to the folklore and rural culture of Ukraine. Like Prymachenko, in fact, Iryna Maksymova often depicts real or fantasy animals (like, for example, the mythical Pegasus of the tapestry of the same name), but endows them with symbolic and sometimes political meanings. Her bestiary composed of sentient creatures, comparable to human beings in a certain sense, actually represents a radical critique of anthropocentric culture, held responsible for the violence perpetrated against animals.

Becoming a Swan, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 140×95 cm

In Maksymova’s work, in certain cases the zoomorphic representation is inserted in the context of precise thematic references – like the swan of the Leda myth (Becoming a Swan) or the biblical tempting snake in Conscience. In other pieces, however, the stimuli come from current events, as in the case of the rooster portrayed in the acrylic on canvas titled Symbol, linking back to the ceramic figurine that became one of the symbols of Ukrainian resistance after the posting of a photo of the destruction at Borodianka that went viral on the web. The image shows a jug with the shape of a rooster, which had remained intact on a kitchen shelf in a bombed-out flat. Curiously enough, that jug with the form of a rooster is a piece by the Ukrainian sculptor Prokop Bidasiuk (1895), whose creations were shown at the Ukrainian National Museum of Decorative Folk Art in Kyiv.

Coscience, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 105×95 cm

As the artist herself puts it, “with my figurative and naïve works I point to the problems of the world that impact me personally, and I attempt to foster equality and interconnection, at the same time developing the traditional motifs of Ukrainian folklore in new visual forms.” As in the painting Holubka Dance, where the motif of the wedding folk dance “Holubka” (which means “female dove”) is transformed into an opportunity to replace the classic paradigm of the couple with a more adventurous orgiastic experience. Another visual theme connected to Ukrainian folklore is that of the berries of the Kalyna, scattered in many of the artist’s works, both in natural botanical form in Mother, Becoming a Swan, Cat and Conscience, and in the guise of pearls for the necklaces worn by her heroines in Don’t Bother, In the Wild Woods and Muses.

The Kalyna (or Viburnum Opulus) is a flowering tree that grows in Ukraine and has been known about since ancient times, when it was believed to have the power of granting immortality and uniting generations in the struggle against evil. Its red berries decorate embroidery, jewelry and even the national costume of Ukrainian women, but above all they are honored in the song Ой у лузі червона калина (“Oh, the Red Viburnum in the Meadow”), a patriotic march written by the composer Stepan Charnetsky in 1914, which then became the anthem of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army from 1918 to 1921. David Gilmour of Pink Floyd created a piece around it, titled Hey, Hey, Rise Up!, also taking inspiration from the a cappella version by the Ukrainian band BoomBox, sung during a tour in the United States precisely on 24 February 2022, the day that marked the beginning of what Putin has euphemistically defined as a “special military operation.”

Odesia, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 195×165 cm

In the works of Iryna Maksymova the symbolism of the Kalyna berries, representing the passion and vitality of the Ukrainian people, also alludes to the bloodshed caused by the war in progress. In general, the symbols used by the artist are always dual, ready for a traditional interpretation but also as a reference to current events and contemporary culture. For example, the creation of tapestries made by hand using fabric remnants is a clear reference to the textile products of Ukrainian folk art, but at the same time it is a sign of the ecological sensibilities of the artist and her desire to avoid any waste through upcycling, a creative practice that unlike ordinary recycling based on the transformation of materials into new products conserves the properties of objects, reutilizing them in such a way that they are clearly recognizable.

Having to utilize the patterns and textures of the fabrics in the tapestries, this is why the gestural aspect of Iryna Maksymova’s painting seems to leave room for the ornamental character typical of traditional textile creations.

The painting titled Odesia, depicting a group of near-naked women sitting on a pile of skulls and framed by bunches of Kalyna berries, can also be interpreted in various ways. On the one hand, the painting reminds us of the typical imagery of the artist, with her exuberant female figures proudly displaying their physical nature; on the other, the work makes explicit reference, straight from the title, to the port city considered the pearl of the Black Sea. Odessa, the historic crossroads between East and West, founded in the 18 th century by a Neapolitan of Spanish origin at what was once the location of the ancient Greek colony of Odessos, has been subjected over the last two years to repeated attacks by Russian planes and missiles. While there is no direct reference to these acts of war in the painting, the question remains: how can we interpret the presence of those skulls?

Motherland, 2024, textile, 195×155 cm

Iryna Maksymova is clearly a painter who relies on symbols and metaphors to narrate a reality, that of today’s Ukraine, suspended between the phantoms of the past, the horrors of the present and hopes for a better future. Her work manages to be political without ever becoming simplistic. Unlike the art produced by many contemporary “artivists,” which is often aesthetically dull or insignificant, her art never gives up on beauty.

The wild, joyful pictorial substance of her paintings and the refined woven patterns of her tapestries are the weapons with which Iryna Maksymova enchants the gaze of observers, while simultaneously making them aware of the dramatic situation in her country. A demonstration of the fact that seduction is almost always the best way to send a message.

INFO:

Irina Maksymova. Landscape’s Body

curated by Ivan Quaroni

Antonio Colombo Artecontemporanea

Milan /Italy

Pegasus, 2024, textile, 145×140 cm